INTERNATIONAL LAW:

International law, also known as public international law and law of nations, is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between nations. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for states across a broad range of domains, including war, diplomacy, trade, and human rights. International law aims to promote the practice of stable, consistent, and organized international relations.

SOURCES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW:

Sources of international law have been influenced by a range of political and legal theories. During the 20th century, it was recognized by legal positivists that a sovereign state could limit its authority to act by consenting to an agreement according to the contract principle pacta sunt servanda. This consensual view of international law was reflected in the 1920 Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice, and remains preserved in Article 7 of the ICJ Statute. The sources of international law applied by the community of nations are listed under Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, which is considered authoritative in this regard:

The sources of international law include international custom (general state practice accepted as law), treaties, and general principles of law recognized by most national legal systems. International law may also be reflected in international comity, the practices and customs adopted by states to maintain good relations and mutual recognition, such as saluting the flag of a foreign ship or enforcing a foreign legal judgment.

International law differs from state-based legal systems in that it is primarily—though not exclusively—applicable to countries, rather than to individuals, and operates largely through consent, since there is no universally accepted authority to enforce it upon sovereign states. Consequently, states may choose to not abide by international law, and even to break a treaty. However, such violations, particularly of customary international law and peremptory norms (jus cogens), can be met with coercive action, ranging from military intervention to diplomatic and economic pressure.

The relationship and interaction between a national legal system (municipal law) and international law is complex and variable. National law may become international law when treaties permit national jurisdiction to supranational tribunals such as the European Court of Human Rights or the International Criminal Court. Treaties such as the Geneva Conventions may require national law to conform to treaty provisions. National laws or constitutions may also provide for the implementation or integration of international legal obligations into domestic law.

Many scholars agree that the fact that the sources are arranged sequentially suggests an implicit hierarchy of sources. However, the language of Article 38 does not explicitly hold such a hierarchy, and the decisions of the international courts and tribunals do not support such a strict hierarchy. By contrast, Article 21 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court clearly defines a hierarchy of applicable law (or sources of international law).

TREATIES:

International treaty law comprises obligations expressly and voluntarily accepted by states between themselves in treaties. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties defines a treaty as follows:

"treaty" means an international agreement concluded between States in written form and governed by international law, whether embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments and whatever its particular designation..This definition has led case-law to define a treaty as an international agreement that meets the following criteria:

Firstly : Requirement of an agreement, meetings of wills (concours de volonté)

Secondly : Requirement of being concluded between subjects of international law: this criterion excludes agreements signed between States and private corporations, such as Production Sharing Agreements. In the 1952 United Kingdom v Iran case, the ICJ did not have jurisdiction for a dispute over the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company being nationalized as the dispute emerged from an alleged breach of contract between a private company and a State.

Firstly : Requirement to be governed by international law: any agreement governed by any domestic law will not be considered a treaty.

Secondly : No requirement of instrument: A treaty can be embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments. This is best exemplified in exchange of letters - (échange de lettres). For example, if France sends a letter to the United States to say, increase their contribution in the budget of the North Atlantic Alliance, and the US accepts the commitment, a treaty can be said to have emerged from the exchange.

Thirdly : No requirement of designation: the designation of the treaty, whether it is a "convention", "pact" or "agreement" has no impact on the qualification of said agreement as being a treaty.

Unwritten Criterion: requirement for the agreement to produce legal effects: this unwritten criterion is meant to exclude agreements which fulfill the above-listed conditions, but are not meant to produce legal effects, such as Memoranda of Understanding.

Where there are disputes about the exact meaning and application of national laws, it is the responsibility of the courts to decide what the law means. In international law, interpretation is within the domain of the states concerned, but may also be conferred on judicial bodies such as the International Court of Justice, by the terms of the treaties or by consent of the parties. Thus, while it is generally the responsibility of states to interpret the law for themselves, the processes of diplomacy and availability of supra-national judicial organs routinely provide assistance to that end.

The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which codifies several bedrock principles of treaty interpretation, holds that a treaty "shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose." This represents a compromise between three different theories of interpretation:

The textual approach, a restrictive interpretation that looks to the "ordinary meaning" of the text, assigning considerable weight to the actual text.

The subjective approach, which takes into consideration factors such as the ideas behind the treaty, the context of the treaty's creation, and what the drafters intended.

The effective approach, which interprets a treaty "in the light of its object and purpose", i.e. based on what best suits the goal of the treaty.

The foregoing are general rules of interpretation, and do no preclude the application of specific rules for particular areas of international law.

Greece v United Kingdom [1952] ICJ 1, ICJ had no jurisdiction to hear a dispute between the UK government and a private Greek businessman under the terms of a treaty.

United Kingdom v Iran [1952] ICJ 2, the ICJ did not have jurisdiction for a dispute over the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company being nationalized.

Oil Platforms case (Islamic Republic of Iran v United States of America) [2003] ICJ 4, rejected dispute over damage to ships which hit a mine.

INTERNATIONAL CUSTOM

Customary international law is derived from the consistent practice of States accompanied by opinio juris, i.e. the conviction of states that the consistent practice is required by a legal obligation. Judgments of international tribunals as well as scholarly works have traditionally been looked to as persuasive sources for custom in addition to direct evidence of state behavior. Attempts to codify customary international law picked up momentum after the Second World War with the formation of the International Law Commission (ILC) under the aegis of the UN. Codified customary law is made the binding interpretation of the underlying custom by agreement through treaty. For states not party to such treaties, the work of the ILC may still be accepted as custom applying to those states. General principles of law are those commonly recognized by the major legal systems of the world. Certain norms of international law achieve the binding force of peremptory norms (jus cogens) as to include all states with no permissible derogations.

Colombia v Perú (1950), recognizing custom as a source of international law, but a practice of giving asylum was not part of it.

Belgium v Spain (1970), finding that only the state where a corporation is incorporated (not where its major shareholders reside) has standing to bring an action for damages for economic loss.

STATEHOOD AND RESPONSIBILITY

The terms monism and dualism are used to describe two different theories of the relationship between international law and national law. Many states, perhaps most, are partly monist and partly dualist in their actual application of international law in their national systems.

MONISM

Monists accept that the internal and international legal systems form a unity. Both national legal rules and international rules that a state has accepted, for example by way of a treaty, determine whether actions are legal or illegal. In most so-called "monist" states, a distinction between international law in the form of treaties, and other international law, e.g., customary international law or jus cogens, is made; such states may thus be partly monist and partly dualist.

In a pure monist state, international law does not need to be translated into national law. It is simply incorporated and has effect automatically in national or domestic laws. The act of ratifying an international treaty immediately incorporates the law into national law; and customary international law is treated as part of national law as well. International law can be directly applied by a national judge, and can be directly invoked by citizens, just as if it were national law. A judge can declare a national rule invalid if it contradicts international rules because, in some states, international rules have priority. In other states, like in Germany, treaties have the same effect as legislation, and by the principle of Lex posterior derogat priori ("Later law removes the earlier"), only take precedence over national legislation enacted prior to their ratification.

In its most pure form, monism dictates that national law that contradicts international law is null and void, even if it post-dates international law, and even if it is constitutional in nature. From a human rights point of view, for example, this has some advantages. For example, a country has accepted a human rights treaty, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, but some of its national laws limit the freedom of the press. A citizen of that country, who is being prosecuted by his state for violating this national law, can invoke the human rights treaty in a national courtroom and can ask the judge to apply this treaty and to decide that the national law is invalid. They do not have to wait for national law that translates international law.

"So when someone in The Netherlands feels his human rights are being violated he can go to a Dutch judge and the judge must apply the law of the Convention. He must apply international law even if it is not in conformity with Dutch law".

DUALISM

Dualists emphasize the difference between national and international law, and require the translation of the latter into the former. Without this translation, international law does not exist as law. International law has to be national law as well, or it is no law at all. If a state accepts a treaty but does not adapt its national law in order to conform to the treaty or does not create a national law explicitly incorporating the treaty, then it violates international law. But one cannot claim that the treaty has become part of national law. Citizens cannot rely on it and judges cannot apply it. National laws that contradict it remain in force. According to dualists, national judges never apply international law, only international law that has been translated into national law.

"International law as such can confer no rights cognisable in the municipal courts. It is only insofar as the rules of international law are recognized as included in the rules of municipal law that they are allowed in municipal courts to give rise to rights and obligations".

The supremacy of international law is a rule in dualist systems as it is in monist systems. Sir Hersch Lauterpacht pointed out the Court's determination to discourage the evasion of international obligations, and its repeated affirmation of: the self-evident principle of international law that a State cannot invoke its municipal law as the reason for the non-fulfillment of its international obligations.

If international law is not directly applicable, as is the case in dualist systems, then it must be translated into national law, and existing national law that contradicts international law must be "translated away". It must be modified or eliminated in order to conform to international law. Again, from a human rights point of view, if a human rights treaty is accepted for purely political reasons, and states do not intend to fully translate it into national law or to take a monist view on international law, then the implementation of the treaty is very uncertain.

International law establishes the framework and the criteria for identifying states as the principal actors in the international legal system. As the existence of a state presupposes control and jurisdiction over territory, international law deals with the acquisition of territory, state immunity and the legal responsibility of states in their conduct with each other. International law is similarly concerned with the treatment of individuals within state boundaries. There is thus a comprehensive regime dealing with group rights, the treatment of aliens, the rights of refugees, international crimes, nationality problems, and human rights generally. It further includes the important functions of the maintenance of international peace and security, arms control, the pacific settlement of disputes and the regulation of the use of force in international relations. Even when the law is not able to stop the outbreak of war, it has developed principles to govern the conduct of hostilities and the treatment of prisoners. International law is also used to govern issues relating to the global environment, the global commons such as international waters and outer space, global communications, and world trade.

In theory all states are sovereign and equal. As a result of the notion of sovereignty, the value and authority of international law is dependent upon the voluntary participation of states in its formulation, observance, and enforcement. Although there may be exceptions, it is thought by many international academics that most states enter into legal commitments with other states out of enlightened self-interest rather than adherence to a body of law that is higher than their own. As D. W. Greig notes, "international law cannot exist in isolation from the political factors operating in the sphere of international relations".

Traditionally, sovereign states and the Holy See were the sole subjects of international law. With the proliferation of international organizations over the last century, they have in some cases been recognized as relevant parties as well. Recent interpretations of international human rights law, international humanitarian law, and international trade law (e.g., North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) Chapter 11 actions) have been inclusive of corporations, and even of certain individuals.

The conflict between international law and national sovereignty is subject to vigorous debate and dispute in academia, diplomacy, and politics. Certainly, there is a growing trend toward judging a state's domestic actions in the light of international law and standards. Numerous people now view the nation-state as the primary unit of international affairs, and believe that only states may choose to voluntarily enter into commitments under international law, and that they have the right to follow their own counsel when it comes to interpretation of their commitments. Certain scholars[who?] and political leaders feel that these modern developments endanger nation states by taking power away from state governments and ceding it to international bodies such as the U.N. and the World Bank, argue that international law has evolved to a point where it exists separately from the mere consent of states, and discern a legislative and judicial process to international law that parallels such processes within domestic law. This especially occurs when states violate or deviate from the expected standards of conduct adhered to by all civilized nations.

A number of states place emphasis on the principle of territorial sovereignty, thus seeing states as having free rein over their internal affairs. Other states oppose this view. One group of opponents of this point of view, including many European nations, maintain that all civilized nations have certain norms of conduct expected of them, including the prohibition of genocide, slavery and the slave trade, wars of aggression, torture, and piracy, and that violation of these universal norms represents a crime, not only against the individual victims, but against humanity as a whole. States and individuals who subscribe to this view opine that, in the case of the individual responsible for violation of international law, he "is become, like the pirate and the slave trader before him, hostis humani generis, an enemy of all mankind", and thus subject to prosecution in a fair trial before any fundamentally just tribunal, through the exercise of universal jurisdiction.

Though the European democracies tend to support broad, universalistic interpretations of international law, many other democracies have differing views on international law. Several democracies, including India, Israel and the United States, take a flexible, eclectic approach, recognizing aspects of international law such as territorial rights as universal, regarding other aspects as arising from treaty or custom, and viewing certain aspects as not being subjects of international law at all. Democracies in the developing world, due to their past colonial histories, often insist on non-interference in their internal affairs, particularly regarding human rights standards or their peculiar institutions, but often strongly support international law at the bilateral and multilateral levels, such as in the United Nations, and especially regarding the use of force, disarmament obligations, and the terms of the UN Charter.

Case Concerning United States Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran [1980] ICJ 1 Democratic Republic of the Congo v Belgium [2002] ICJ 1TERRITORY AND THE LAW OF SEA

Among the earliest examples of legal codes concerning maritime affairs is the Byzantine Lex Rhodia, promulgated between 600 and 800 C.E. to govern trade and navigation in the Mediterranean. Maritime law codes were also created during the European Middle Ages, such as the Rolls of Oléron, which drew from Lex Rhodia, and the Laws of Wisby, enacted among the mercantile city-states of the Hanseatic League.

However, the earliest known formulation of public international law of the sea was in 17th century Europe, which saw unprecedented navigation, exploration, and trade across the world's oceans. Portugal and Spain led this trend, staking claims over both the land and sea routes they discovered. Spain considered the Pacific Ocean a mare clausum—literally a "closed sea" off limits to other naval powers—in part to protect its the possessions in Asia. Similarly, as the only known entrance from the Atlantic, the Strait of Magellan was periodically patrolled by Spanish fleets to prevent entrance by foreign vessels. The papal bull Romanus Pontifex (1455) recognized Portugal's exclusive right to navigation, trade, and fishing in the seas near discovered land, and on this basis the Portuguese claimed a monopoly on East Indian trade, prompting opposition and conflict from other European naval powers.

Amid growing competition over sea trade, Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius—considered the father of international law generally—wrote Mare Liberum (The Freedom of the Seas), published in 1609, which set forth the principle that the sea was international territory and that all nations were thus free to use it for trade. He premised this argument on the idea that "every nation is free to travel to every other nation, and to trade with it." Thus, there was a right to innocent passage over land and a similar right of innocent passage at sea. Grotius observed that unlike land, on which sovereigns could demarcate their jurisdiction, the sea was akin to air, a common property of all:

The air belongs to this class of things for two reasons. First, it is not susceptible of occupation; and second its common use is destined for all men. For the same reasons the sea is common to all, because it is so limitless that it cannot become a possession of any one, and because it is adapted for the use of all, whether we consider it from the point of view of navigation or of fisheries.

Writing in response to Grotius, the English jurist John Selden argued in Mare Clausum that the sea was as capable of appropriation by sovereign powers as terrestrial territory. Rejecting Grotius' premise, Selden claimed there was no historical basis for the sea to be treated differently than land, nor was there anything inherent in the nature of the sea that precluded states from exercising dominion over parts of it. In essence, international law could evolve to accommodate the emerging framework of national jurisdiction over the sea.

As a growing number of nations began to expand their naval presence across the world, conflicting claims over the open sea mounted. This prompted maritime states to moderate their stance and to limit the extent of their jurisdiction towards the sea from land. This was aided by the compromise position presented by Dutch legal theorist Cornelius Bynkershoek, who in De dominio maris (1702), established the principle that maritime dominion was limited to the distance within which cannons could effectively protect it.

Grotius' concept of "freedom of the seas" became virtually universal through the 20th century, following the global dominance of European naval powers. National rights and jurisdiction over the seas were limited to a specified belt of water extending from a nation's coastlines, usually three nautical miles (5.6 km), according to Bynkershoek's "cannon shot" rule.[9] Under the mare liberum principle, all waters beyond national boundaries were considered international waters: Free to all nations, but belonging to none of them.

In the early 20th century, some nations expressed their desire to extend national maritime claims, namely to exploit mineral resources, protect fish stocks, and enforce pollution controls. To that end, in 1930, the League of Nations called conference at The Hague, but no agreements resulted. By the mid 20th century, technological improvements in fishing and oil exploration expanded the nautical range in which countries could detect and exploit natural resources. This prompted United States President Harry S. Truman in 1945 to extend American jurisdiction to all the natural resources of its continental shelf, well beyond the territorial waters of the country. Truman's proclamation cited the customary international law principle of a nation's right to protect its natural resources. Other nations quickly followed suit: Between 1946 and 1950, Chile, Peru, and Ecuador extended their rights to a distance of 200 nautical miles (370 km) to cover their Humboldt Current fishing grounds.

UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION OF THE LAW OF THE SEA

The first attempt to promulgate and codify a comprehensive law of the sea was in the 1950s, shortly after the Truman proclamation on the continental shelf. In 1956, the United Nations held its first Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS I) in Geneva, Switzerland, which resulted in four treaties concluded in 1958:

Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone, entry into force: 10 September 1964

Convention on the Continental Shelf, entry into force: 10 June 1964

Convention on the High Seas, entry into force: 30 September 1962

Convention on Fishing and Conservation of Living Resources of the High Seas, entry into force: 20 March 1966

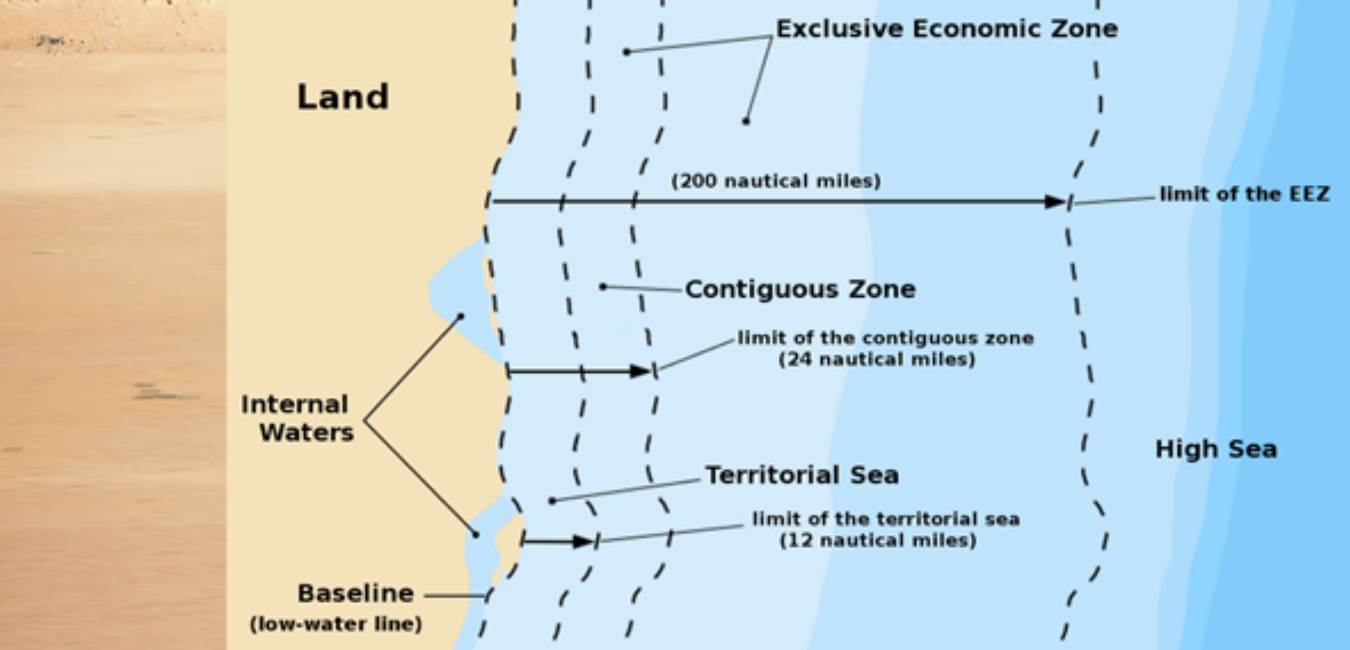

(Maritime zones are a core component of modern law of the sea.)

The Convention on the Continental Shelf effectively codified Truman's proclamation as customary international law. While UNCLOS I was widely considered a success, it left open the important issue of the extent of territorial waters. In 1960, the UN held a second Conference on the Law of the Sea ("UNCLOS II"), but this did not result in any new agreements. The pressing issue of varying claims of territorial waters was raised at the UN in 1967 by Malta, prompting in 1973 a third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea in New York City. In an attempt to reduce the possibility of groups of nation-states dominating the negotiations, the conference used a consensus process rather than majority vote. With more than 160 nations participating, the conference lasted until 1982, resulting in the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea, also known as the Law of the Sea Treaty, which defines the rights and responsibilities of nations in their use of the world's oceans.

UNCLOS introduced a number of provisions, of which the most significant concerned navigation, archipelagic status and transit regimes, exclusive economic zones (EEZs), continental shelf jurisdiction, deep seabed mining, the exploitation regime, protection of the marine environment, scientific research, and settlement of disputes. It also set the limit of various areas, measured from a carefully defined sea baseline.

The convention also codified freedom of the sea, explicitly providing that the oceans are open to all states, with no state being able to subject any part to its sovereignty. Consequently, state parties cannot unilaterally extend their sovereignty beyond their EEZ, the 200 nautical miles in which that state has exclusive rights to fisheries, minerals, and sea-floor deposits. "Innocent passage" is permitted through both territorial waters and the EEZ, even by military vessels, provided they do no harm to the country or break any of its laws.

PARTIES TO THE UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE LAW OF THE SEA (as of June 2019).

The convention came into force on 16 November 1994, one year after it was ratified by the 60th state, Guyana; the four treaties concluded in the first UN Conference in 1956 were consequently superseded. As of June 2019, UNCLOS has been ratified by 168 states. Many of the countries that have not ratified the treaty, such as the U.S., nonetheless recognize its provisions as reflective of international customary law. Thus, it remains the most widely recognized and followed source of international law with respect to the sea.

Between 2018 and 2020, there is a conference on a possible change to the law of the sea regarding conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (General Assembly resolution 72/249).

RECOGNITION AND ENFORCEMENT OF LAW OF THE SEA:

Although UNCLOS was created under the auspices of the UN, the organization has no direct operational role in its implementation. However, a specialized agency of the UN, the International Maritime Organization, plays a role in monitoring and enforcing certain provisions of the convention, along with the intergovernmental International Whaling Commission, and the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which was established by the convention to organize, regulate and control all mineral-related activities in the international seabed area beyond territorial limits.

UNCLOS established the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), based in Hamburg, Germany, to adjudicate all disputes concerning the interpretation or application of the convention (subject to the provisions of Article 297 and to the declarations made in accordance with article 298 of the convention). Its 21 judges are drawn from a wide variety of nations. Because the EEZ is so extensive, many ITLOS cases concern competing claims over the ocean boundaries between states As of 2017, ITLOS had settled 25 cases.

MARITIME LAW

Law of the Sea should be distinguished from Maritime Law, which concerns maritime issues and disputes among private parties, such as individuals, international organizations, or corporations. However, the International Maritime Organisation, a UN agency that plays a major role in implementing law of the sea, also helps to develop, codify, and regulate certain rules and standards of Maritime Law.

The law of the sea is the area of international law concerning the principles and rules by which states and other entities interact in maritime matters.[33] It encompasses areas and issues such as navigational rights, sea mineral rights, and coastal waters jurisdiction. The law of the sea is distinct from Admiralty Law (also known as Maritime Law), which concerns relations and conduct at sea by private entities.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), concluded in 1982 and coming into force in 1994, is generally accepted as a codification of customary international law of the sea.

TERRITORIAL DISPUTE:

Libya v Chad [1994] ICJ 1

United Kingdom v Norway [1951] ICJ 3, the Fisheries case, concerning the limits of Norway's jurisdiction over neighboring waters

Peru v Chile (2014) dispute over international waters.

Bakassi case [2002] ICJ 2, between Nigeria and Cameroon

Burkina Faso-Niger frontier dispute case (2013)

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

Corfu Channel Case [1949] ICJ 1, UK sues Albania for damage to ships in international waters. First ICJ decision.

France v United Kingdom [1953] ICJ 3

Germany v Denmark and the Netherlands [1969] ICJ 1, successful claim for a greater share of the North Sea continental shelf by Germany. The ICJ held that the matter ought to be settled, not according to strict legal rules, but through applying equitable principles.

Case concerning maritime delimitation in the Black Sea (Romania v Ukraine) [2009] ICJ 3

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

INTERGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATION & GLOBAL ADMINISTRATIVE LAW:

1)United Nations

2)World Trade Organization

3)International Labour Organization

4)NATO

5)European Union

6) G7 and G20

7) OPEC

8) Organisation of Islamic Conference

9) Food and Agriculture Organization

10)World Health Organization

11)Social and economic policy

CONFLICTS OF LAWS

Netherlands v Sweden [1958] ICJ 8, Sweden had jurisdiction over its guardianship policy, meaning that its laws overrode a conflicting guardianship order of the Netherlands.

Liechtenstein v Guatemala [1955] ICJ 1, the recognition of Mr Nottebohm's nationality, connected to diplomatic protection.

Italy v France, United Kingdom and United States [1954] ICJ 2

HUMAN RIGHTS

Main articles: International human rights law and Human rights

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Croatia–Serbia genocide case (2014) ongoing claims over genocide.

Bosnia and Herzegovina v Serbia and Montenegro [2007] ICJ 2

Case Concerning Barcelona Traction, Light, and Power Company, Ltd [1970] ICJ 1

LABOR LAW

a) International labour law and Labour law b) International Labor Organization c) ILO Conventions d) Declaration of Philadelphia of 1944 e) Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work of 1998 f) United Nations Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families g) The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination 1965 h) Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women 1981); i) The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2008

DEVELOPMENT AND FINANCE:

a) International development, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund b) Bretton Woods Conference c) World Bank d) International Monetary Fund

ENVIRONMENTAL LAW

International environmental law and Environmental law

TRADE

a) World Trade Organization

b) World Trade Organization

Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): The TPP is a proposed free trade agreement among 11 Pacific Rim economies, focusing on tariff reductions. It was the centerpiece of President Barack Obama's strategic pivot to Asia. Before President Donald J. Trump withdrew the United States in 2017, the TPP was set to become the world's largest free trade deal, covering 40 percent of the global economy.

Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP): The RCEP is a free trade agreement between the Asia-Pacific nations of Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam. It includes the 10 ASEAN members plus 6 ASEAN foreign partners. The 16 nations signed the agreement on November 15, 2020, via tele-conference. The deal excludes the US, which withdrew from a rival Asia-Pacific trade pact in 2017. RCEP will connect about 30% of the world's people and output and, in the right political context, will generate significant gains. RCEP aims to create an integrated market with 16 countries, making it easier for products and services of each of these countries to be available across this region. The negotiations are focused on the following: Trade in goods and services, investment, intellectual property, dispute settlement, e-commerce, small and medium enterprises, and economic cooperation.

LAW OF WAR

Nicaragua v. United States [1986] ICJ 1 International Court of Justice advisory opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons

HUMANITARIAN LAW

a) International humanitarian law b) Geneva conventions First Geneva Convention of 1949, Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field, (first adopted in 1864) Second Geneva Convention of 1949, Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea (first adopted in 1906) Third Geneva Convention of 1949, Treatment of Prisoners of War, adopted in 1929, following from the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War.

INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL LAW

International criminal law and International Criminal Court

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT

International Court of Justice

It is probably the case that almost all nations observe almost all principles of international law and almost all of their obligations almost all the time.

Since international law has no established compulsory judicial system for the settlement of disputes or a coercive penal system, it is not as straightforward as managing breaches within a domestic legal system. However, there are means by which breaches are brought to the attention of the international community and some means for resolution. For example, there are judicial or quasi-judicial tribunals in international law in certain areas such as trade and human rights. The formation of the United Nations, for example, created a means for the world community to enforce international law upon members that violate its charter through the Security Council.

Since international law exists in a legal environment without an overarching "sovereign" (i.e., an external power able and willing to compel compliance with international norms), "enforcement" of international law is very different from in the domestic context. In many cases, enforcement takes on Coasian characteristics, where the norm is self-enforcing. In other cases, defection from the norm can pose a real risk, particularly if the international environment is changing. When this happens, and if enough states (or enough powerful states) continually ignore a particular aspect of international law, the norm may actually change according to concepts of customary international law. For example, prior to World War I, unrestricted submarine warfare was considered a violation of international law and ostensibly the casus belli for the United States' declaration of war against Germany. By World War II, however, the practice was so widespread that during the Nuremberg trials, the charges against German Admiral Karl Dönitz for ordering unrestricted submarine warfare were dropped, notwithstanding that the activity constituted a clear violation of the Second London Naval Treaty of 1936.

DOMESTIC ENFORCEMENT

Apart from a state's natural inclination to uphold certain norms, the force of international law comes from the pressure that states put upon one another to behave consistently and to honor their obligations. As with any system of law, many violations of international law obligations are overlooked. If addressed, it may be through diplomacy and the consequences upon an offending state's reputation, submission to international judicial determination, arbitration,] sanctions or force including war. Though violations may be common in fact, states try to avoid the appearance of having disregarded international obligations. States may also unilaterally adopt sanctions against one another such as the severance of economic or diplomatic ties, or through reciprocal action. In some cases, domestic courts may render judgment against a foreign state (the realm of private international law) for an injury, though this is a complicated area of law where international law intersects with domestic law.

It is implicit in the Westphalian system of nation-states, and explicitly recognized under Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, that all states have the inherent right to individual and collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against them. Article 51 of the UN Charter guarantees the right of states to defend themselves until (and unless) the Security Council takes measures to keep the peace.

INTERNATIONAL BODIES

a) International legal system and

b) United Nations General Assembly Resolution 377

As a "deliberative, policymaking and representative organ", the United Nations General Assembly "is empowered to make recommendations"; it can neither codify international law nor make binding resolutions. Merely internal resolutions, such as budgetary matters, may be binding on the operation of the General Assembly itself. Violations of the UN Charter by members of the United Nations may be raised by the aggrieved state in the General Assembly for debate.

General Assembly resolutions are generally non-binding towards member states, but through its adoption of the "Uniting for Peace" resolution (A/RES/377 A), of 3 November 1950, the Assembly declared that it had the power to authorize the use of force, under the terms of the UN Charter, in cases of breaches of the peace or acts of aggression, provided that the Security Council, owing to the negative vote of a permanent member, fails to act to address the situation. The Assembly also declared, by its adoption of resolution 377 A, that it could call for other collective measures—such as economic and diplomatic sanctions—in situations constituting the milder "threat to the Peace".

The Uniting for Peace resolution was initiated by the United States in 1950, shortly after the outbreak of the Korean War, as a means of circumventing possible future Soviet vetoes in the Security Council. The legal role of the resolution is clear, given that the General Assembly can neither issue binding resolutions nor codify law. It was never argued by the "Joint Seven-Powers" that put forward the draft resolution, during the corresponding discussions, that it in any way afforded the Assembly new powers. Instead, they argued that the resolution simply declared what the Assembly's powers already were, according to the UN Charter, in the case of a dead-locked Security Council. The Soviet Union was the only permanent member of the Security Council to vote against the Charter interpretations that were made recommendation by the Assembly's adoption of resolution 377 A.

Alleged violations of the Charter can also be raised by states in the Security Council. The Security Council could subsequently pass resolutions under Chapter VI of the UN Charter to recommend the "Pacific Resolution of Disputes." Such resolutions are not binding under international law, though they usually are expressive of the council's convictions. In rare cases, the Security Council can adopt resolutions under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, related to "threats to Peace, Breaches of the Peace and Acts of Aggression," which are legally binding under international law, and can be followed up with economic sanctions, military action, and similar uses of force through the auspices of the United Nations.

It has been argued that resolutions passed outside of Chapter VII can also be binding; the legal basis for that is the council's broad powers under Article 24(2), which states that "in discharging these duties (exercise of primary responsibility in international peace and security), it shall act in accordance with the Purposes and Principles of the United Nations". The mandatory nature of such resolutions was upheld by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in its advisory opinion on Namibia. The binding nature of such resolutions can be deduced from an interpretation of their language and intent.

States can also, upon mutual consent, submit disputes for arbitration by the International Court of Justice, located in The Hague, Netherlands. The judgments given by the court in these cases are binding, although it possesses no means to enforce its rulings. The Court may give an advisory opinion on any legal question at the request of whatever body may be authorized by or in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations to make such a request. Some of the advisory cases brought before the court have been controversial with respect to the court's competence and jurisdiction.

Often enormously complicated matters, ICJ cases (of which there have been less than 150 since the court was created from the Permanent Court of International Justice in 1945) can stretch on for years and generally involve thousands of pages of pleadings, evidence, and the world's leading specialist international lawyers. As of November 2019, there are 16 cases pending at the ICJ. Decisions made through other means of arbitration may be binding or non-binding depending on the nature of the arbitration agreement, whereas decisions resulting from contentious cases argued before the ICJ are always binding on the involved states.

Though states (or increasingly, international organizations) are usually the only ones with standing to address a violation of international law, some treaties, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights have an optional protocol that allows individuals who have had their rights violated by member states to petition the international Human Rights Committee. Investment treaties commonly and routinely provide for enforcement by individuals or investing entities. and commercial agreements of foreigners with sovereign governments may be enforced on the international plane.

INTERNATIONAL COURTS:

There are numerous international bodies created by treaties adjudicating on legal issues where they may have jurisdiction. The only one claiming universal jurisdiction is the United Nations Security Council. Others are: the United Nations International Court of Justice, and the International Criminal Court (when national systems have totally failed and the Treaty of Rome is applicable) and the Court of Arbitration for Sport.

EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY

East African Community There were ambitions to make the East African Community, consisting of Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi and Rwanda, a political federation with its own form of binding supranational law, but this effort has not materialized.

UNION OF SOUTH AMERICAN NATIONS

Union of South American Nations

The Union of South American Nations serves the South American continent. It intends to establish a framework akin to the European Union by the end of 2019. It is envisaged to have its own passport and currency, and limit barriers to trade.

ANDEAN COMMUNITY OF NATIONS

Andean Community of Nations

The Andean Community of Nations is the first attempt to integrate the countries of the Andes Mountains in South America. It started with the Cartagena Agreement of 26 May 1969, and consists of four countries: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. The Andean Community follows supranational laws, called Agreements, which are mandatory for these countries.

INTERNATIONAL LEGAL THEORY

International legal theories

International legal theory comprises a variety of theoretical and methodological approaches used to explain and analyse the content, formation and effectiveness of international law and institutions and to suggest improvements. Some approaches center on the question of compliance: why states follow international norms in the absence of a coercive power that ensures compliance. Other approaches focus on the problem of the formation of international rules: why states voluntarily adopt international law norms, that limit their freedom of action, in the absence of a world legislature; while other perspectives are policy oriented: they elaborate theoretical frameworks and instruments to criticize the existing norms and to make suggestions on how to improve them. Some of these approaches are based on domestic legal theory, some are interdisciplinary, and others have been developed expressly to analyse international law. Classical approaches to International legal theory are the Natural law, the Eclectic and the Legal positivism schools of thought.

The natural law approach argues that international norms should be based on axiomatic truths. 16th-century natural law writer, Francisco de Vitoria, a professor of theology at the University of Salamanca, examined the questions of the just war, the Spanish authority in the Americas, and the rights of the Native American peoples.

In 1625 Hugo Grotius argued that nations as well as persons ought to be governed by universal principle based on morality and divine justice while the relations among polities ought to be governed by the law of peoples, the jus gentium, established by the consent of the community of nations on the basis of the principle of pacta sunt servanda, that is, on the basis of the observance of commitments. On his part, Emmerich de Vattel argued instead for the equality of states as articulated by 18th-century natural law and suggested that the law of nations was composed of custom and law on the one hand, and natural law on the other. During the 17th century, the basic tenets of the Grotian or eclectic school, especially the doctrines of legal equality, territorial sovereignty, and independence of states, became the fundamental principles of the European political and legal system and were enshrined in the 1648 Peace of Westphalia.

The early positivist school emphasized the importance of custom and treaties as sources of international law. 16th-century Alberico Gentili used historical examples to posit that positive law (jus voluntarium) was determined by general consent. Cornelius van Bynkershoek asserted that the bases of international law were customs and treaties commonly consented to by various states, while John Jacob Moser emphasized the importance of state practice in international law. The positivism school narrowed the range of international practice that might qualify as law, favouring rationality over morality and ethics. The 1815 Congress of Vienna marked the formal recognition of the political and international legal system based on the conditions of Europe.

Modern legal positivists consider international law as a unified system of rules that emanates from the states' will. International law, as it is, is an "objective" reality that needs to be distinguished from law "as it should be." Classic positivism demands rigorous tests for legal validity and it deems irrelevant all extralegal arguments.

t>